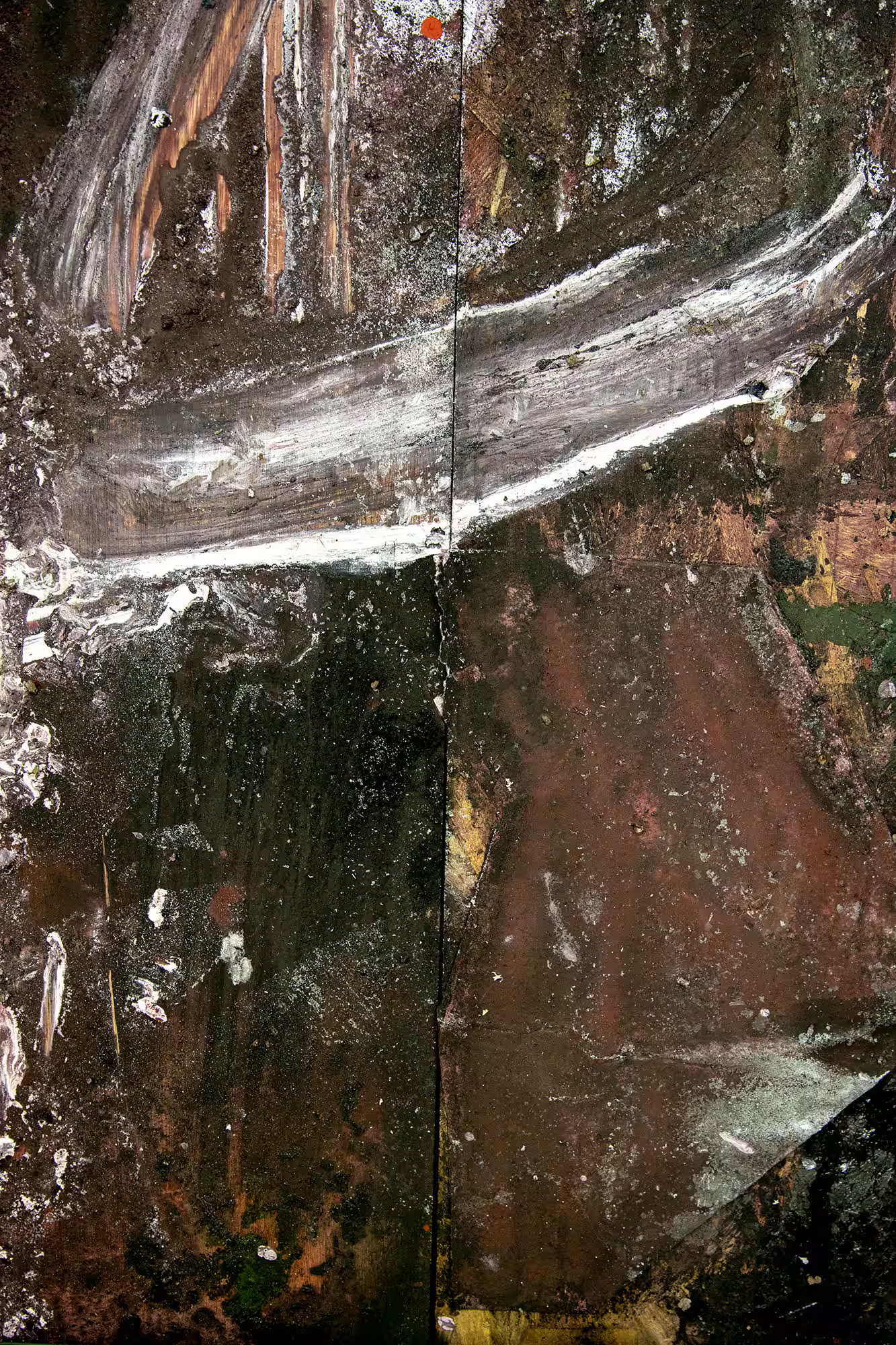

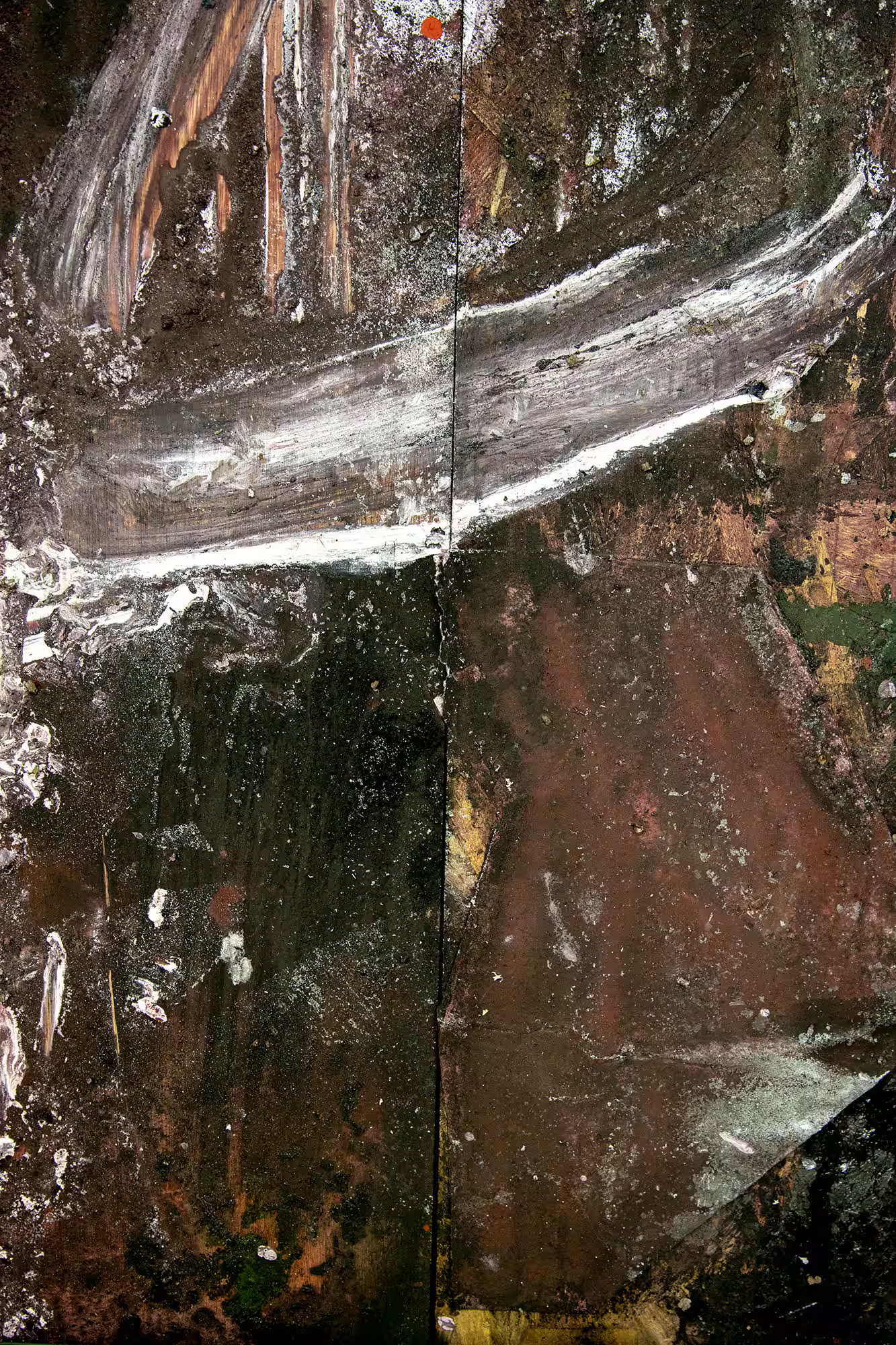

Samuel Ross, CAVE-1A, 2025. Image courtesy of the artist.

Though generations apart, Samuel Ross and Takashi Murakami fluidly move between disciplines—fine art, fashion, design, tech—without ever being confined by them. Their practices aren’t just expansive so much as deliberate exercises in adaptation, strategy, and reinvention. Ross resists categorization—an instinct that has made him one of his generation’s most formidable creative forces. His brutalist, materially driven design ethos shaped A-COLD-WALL, a fashion brand that dissected class, utility, and the evolving relationship between streetwear and luxury, while reframing performancewear as a medium for cultural commentary. Now, through SR_A, his multidisciplinary practice, The London-based artist, 33, applies that same intellectual rigor to architecture, industrial design, and contemporary art, exploring the tension between luxury, function, and conceptual form.

Known for his psychedelic colors, anime-inspired characters, signature smiling flowers, and his hyper-stylized aesthetic, Murakami, 63, pioneered Superflat, a theory-turned-movement that redefined Japanese visual culture. Emerging in 2000 as both an exhibition and philosophy, Superflat collapses distinctions between high art and pop culture, fine art and mass production, drawing from Edoperiod ukiyo-e, postwar anime, and the hypercommerciality of modern Japan. His work spans from Gagosian’s gallery walls to Louis Vuitton handbags, museum installations to N.F.T.s, constantly navigating the spectrum between accessibility and exclusivity. Murakami calls his process “chaos.” Ross describes structure as something to challenge, not obey. For each, agency isn’t about maintaining order; it’s about knowing when to let go, when to shift, when to disrupt.

Samuel Ross, HEART-1, 2025. Image courtesy of the artist.

Samuel Ross: Hello.

Takashi Murakami: Oh, Samuel-san. Good day.

SR: It’s good to see you.

TM: We just missed each other in Paris... Same hotel, right?

SR: Exactly. We had a show out there, and it went super well. Now I am in Savannah; we opened “HEAVE” [at SCAD Museum of Art]. It is the first American museum show I’ve had where they’re showing fashion, sculpture, and painting together. You said something recently about how social media finally made the world Superflat, and I’ve been thinking about that the past few days. It used to be this insane rabbit hole of being able to speak to people that you have natural affinity with culturally, philosophically, artistically. And then Instagram came along, post-Tumblr, and flattened all of that, enabling artists, designers, and thinkers to connect to one another. I always find that the strongest and most heartfelt rapports between artists are also the most organic.

TM: I first found you on Instagram in 2017. I asked you to make a piece for me. What’s your activity looking like now? My understanding is that you’re focusing more on fine art than fashion?

SR: I started A-COLD-WALL independently in a council estate in the U.K., and I built a core team quite early on. We were all under 25. When we got to year three, we took on a minority shareholder. As A-COLD-WALL started to grow, we started to open physical retail doors globally, and by 2022 we had about six. We started to mature, and at that point we reached around 45 product releases, primarily footwear, solely between Nike and Converse. It gave me the freedom and the peace of mind to be able to think about how to split my time 50 percent between the arts and 50 percent between fashion. Today, I mainly show with a few select galleries such as Friedman Benda and White Cube, but I’m also focused on institutional placements. Some sculptures, paintings, and garments have been acquired by The Met in New York, the V&A in London, the SCAD Museum, and the Dallas Museum of Art. It’s given me the opportunity to have a long-form conversation in the arts while also focusing on restoring craft in fashion, moving away from a rapid pace, and really focusing on couture.

TM: So does that mean you can make enough money on the art side?

SR: Well, we’re on a journey. We’re about to take this really fantastic lake house in the countryside, and we’ll still keep a beautiful studio in North London in Islington. It’s the best of both worlds—between art, industrial design, and fashion. It feels like a really modern way to exist and thrive as an artist.

Samuel Ross, LUCID-1, 2025. Image courtesy of the artist.

TM: The majority of my money comes from my art practice, but the art market can always go down, so I have to do a lot of different things in order to survive. Two years ago, I survived through exploring N.F.T.s, and before that I survived by selling a lot of prints. More recently, I revived the collaboration with Louis Vuitton. Then there are many other different projects happening. But in order to do something I really want to do, of course, I have to fund it, and then in order to do that, I have to do so many different things.

SR: I went to your show [“Japanese Art History à la Takashi Murakami”] in London at Gagosian, too. The work is fantastic. I can see the continuity between what you do there, what you do with Vuitton, what you do with Hublot, what you do independently, what you do in animation and N.F.T.s, and it’s so clear. How do you go about controlling all of those different aspects and protecting your brand’s world?

TM: I have no control whatsoever. I’m always out of control, and even now I am so confused and writing down what I have to do.

SR: I’ve found that when there’s the least control, that’s when the real ideas come about. Whether we’re talking philosophically or spiritually or creatively or commercially. It’s that one lucid sketch out of 400 where you just don’t care and you’ve completely disbanded any idea of trying to produce good work. As soon as you design and you relinquish control, then there is a breakthrough of sorts. Structure is a tension point you need to push and pull against. It’s a counter way more so than an architecture that you operate between. You work with individuals that understand one another and who each have their own domain of expertise. Together you establish infrastructure and structure, but you can’t both push against the same wall. You need one person pushing against one wall and another pushing against the other wall, and then you have stability I’d say. It’s all about these relationships and trust.

TM: I really don’t understand what balance is and should be. I really have no idea, which is why I employ so many people. Every day it’s chaos, and we just keep going at it. It’s not a very effective way of doing things, but that’s how I do it...

SR: I have two daughters, 7 and 3. They’re starting to ask questions about how my time is spent. I don’t know what work actually is or what that term means. We have a life, and we pour our spirit and our soul into our output, and that chaos feels right to follow. I couldn’t see another way. Maybe I’ve been partly blindsided because, for the last 14 years, almost half my life has looked like this. And for you, Takashi-san, even more of your time has looked like this. It’s just a way of seeing, living, and breathing.

TM: My brain can’t focus on one thing. I can’t think logically about switching creative disciplines.

SR: It’s more like an impulse, and then we need people to help us structure the impulses. Because at times there’s something interesting within the impulse itself. The ideas just fly out, and you need to catch them and see what sticks—see what’s a pile of shit and doesn’t work, and see where there’s actually something quite magnificent that others will see life in.

Samuel Ross, WITHOUT SILT-1, 2025. Image courtesy of the artist.

TM: About 85 percent of what I do is commercial-facing, and I don’t feel any guilt over it. Then there’s about 15 percent that I do completely freely, without care of it selling or not. But in order to do this, I need to do the 85 percent.

SR: Nothing is for free, right? In terms of time or liberation within the arts. I don’t feel like there’s a hierarchy between creating an abstract, orange smart-toilet for Salone [del Mobile] or an abstract sculpture carved of British marble in Chatsworth House or a kid wearing an amazing hoodie that we’ve spent six months perfecting. You get elected by the people as an artist, so you need to make sure that you take care of them as well. In return, they give you space to produce works that are pure. That’s the way I look at it: You’re just turning the dial on how that emotion takes shape, whether it’s really radical like a bleeding synth or whether it’s more of an accessible sound like an orchestra, which might be deemed commercial. But again, there’s no hierarchy between the two.

TM: That’s a really clear and amazing explanation.

SR: What were key moments in your career that really stand out to you?

TM: First and foremost is definitely Superflat. When I created an exhibition that pushed that idea out, and also published a book on that theory, that was a big turning point in my career.

SR: Making a book still feels like a superpower. It is the perfect medium between pop, society, academia, and being able to validate ideas. There’s so much space for artists of new generations to tap into this idea of the artist’s manifesto and really own what is theirs through print. I think saying that a printed manifesto being this opening for you feels quite significant for younger artists to hear.

TM: It looks like you’re the teacher and I’m the student.

SR: No, no, no. I’m trying to learn how to simplify and how to make sure that everything is well understood, but also learning from you—the book you mentioned is really significant because that’s how I first came to your work. The importance of artists like yourself is showing and liberating others to be able to work across all these different mediums. There are no boundaries.

Samuel Ross, NO MOUNTAIN-1, 2025. Image courtesy of the artist.

TM: In my lifetime, there have been four drastic changes that happened. First was the Apple II computer emergence, the second was the World Wide Web, and then the third was social media. Now it’s A.I. Each time, everyone had to change everything. Some people of my generation couldn’t get into the computer thing. They didn’t want to deal with it. Then, of course, many people of my generation had negative feelings about social media, so they didn’t get involved. People are resistant to A.I., but I’ve been enjoying making music with it. The experience is super fresh.

SR: It’s interesting because it feels like with A.I., there’s this way to bring new life to the storytelling.

TM: The fine-art world is having an animation effect.

SR: Are you doing A.I. animation as well?

TM: I cannot do it myself, but I employ several assistants.

SR: I used to study animation in school many years ago, and you used to have to update every single frame. Now you don’t need as much labor to animate something.

TM: The way of doing things constantly changes. So, for example, maybe I.P. itself will become obsolete because everything will become public domain—and if you want to protect it, only the lawyers will make money, not the creators. On the other hand, maybe A.I. will come up with some ways to fairly divide the profit from one’s I.P. You can’t really predict it, so what I can do is follow all the developments as much as I can and try to understand it and use it for my next creations. Because the next generation will be living in that reality, so if you’re not embracing it, your work will be obsolete.

SR: It’s a fine line of keeping up with what’s happening in the technological trend cycle and making sure the work is actually speaking to and representing the people.