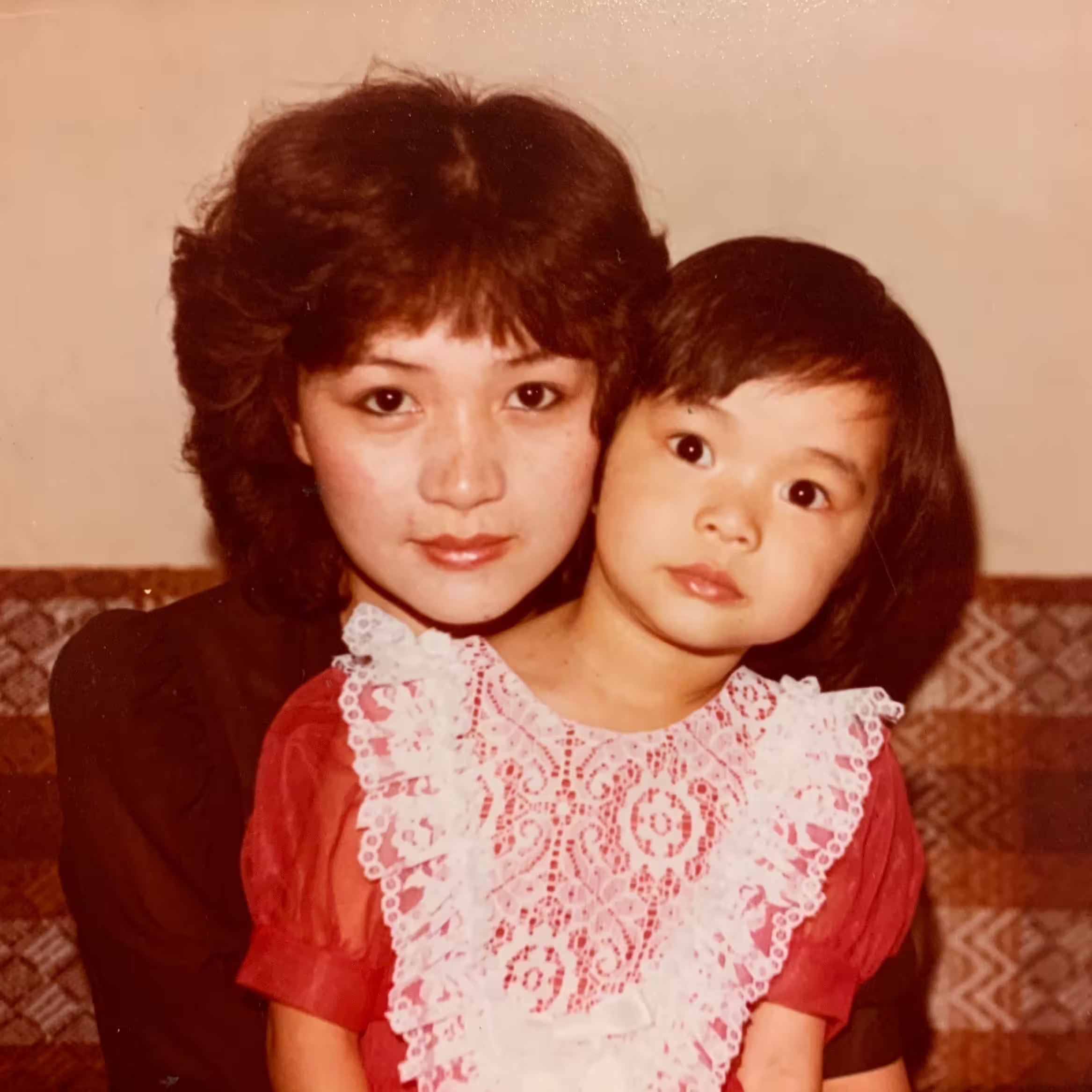

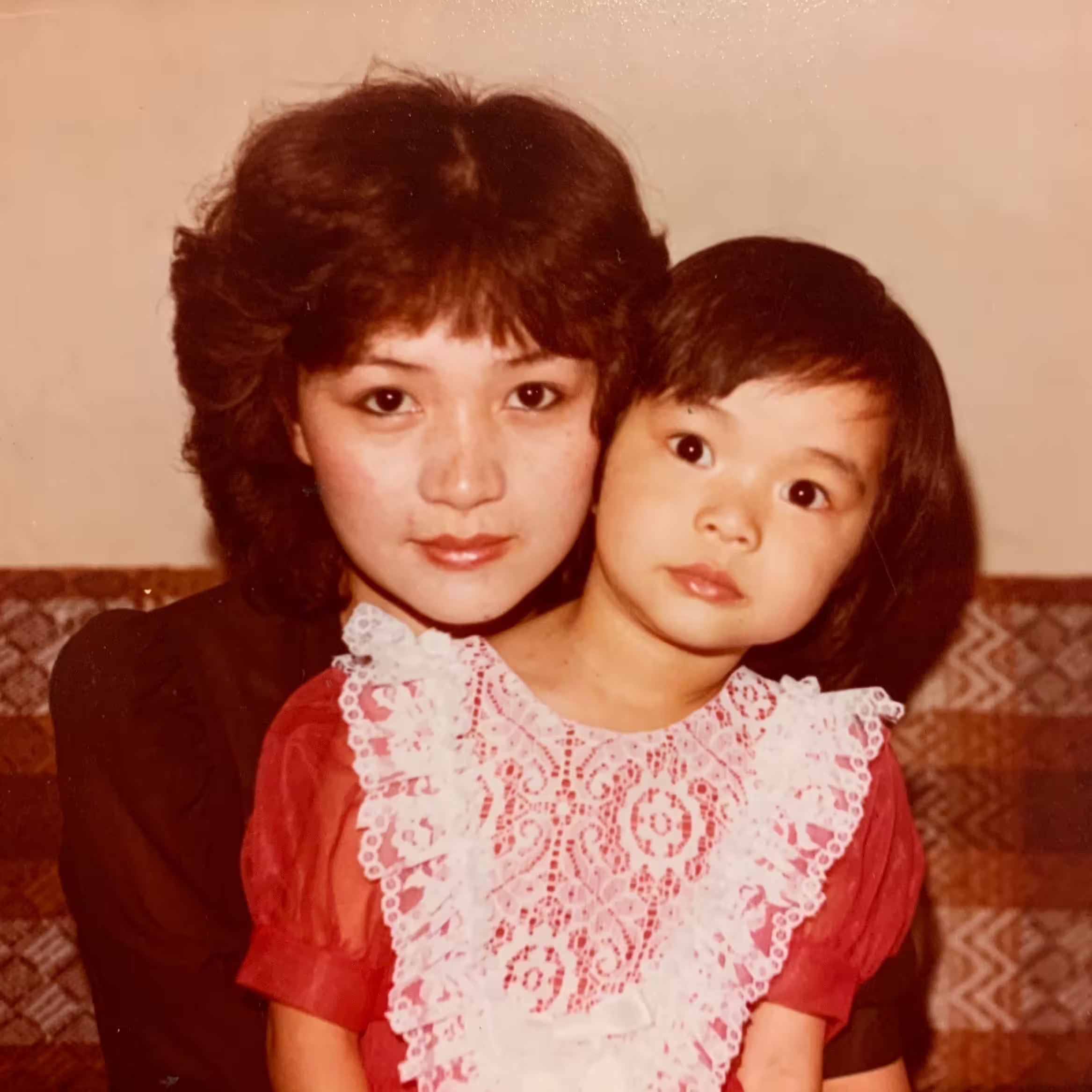

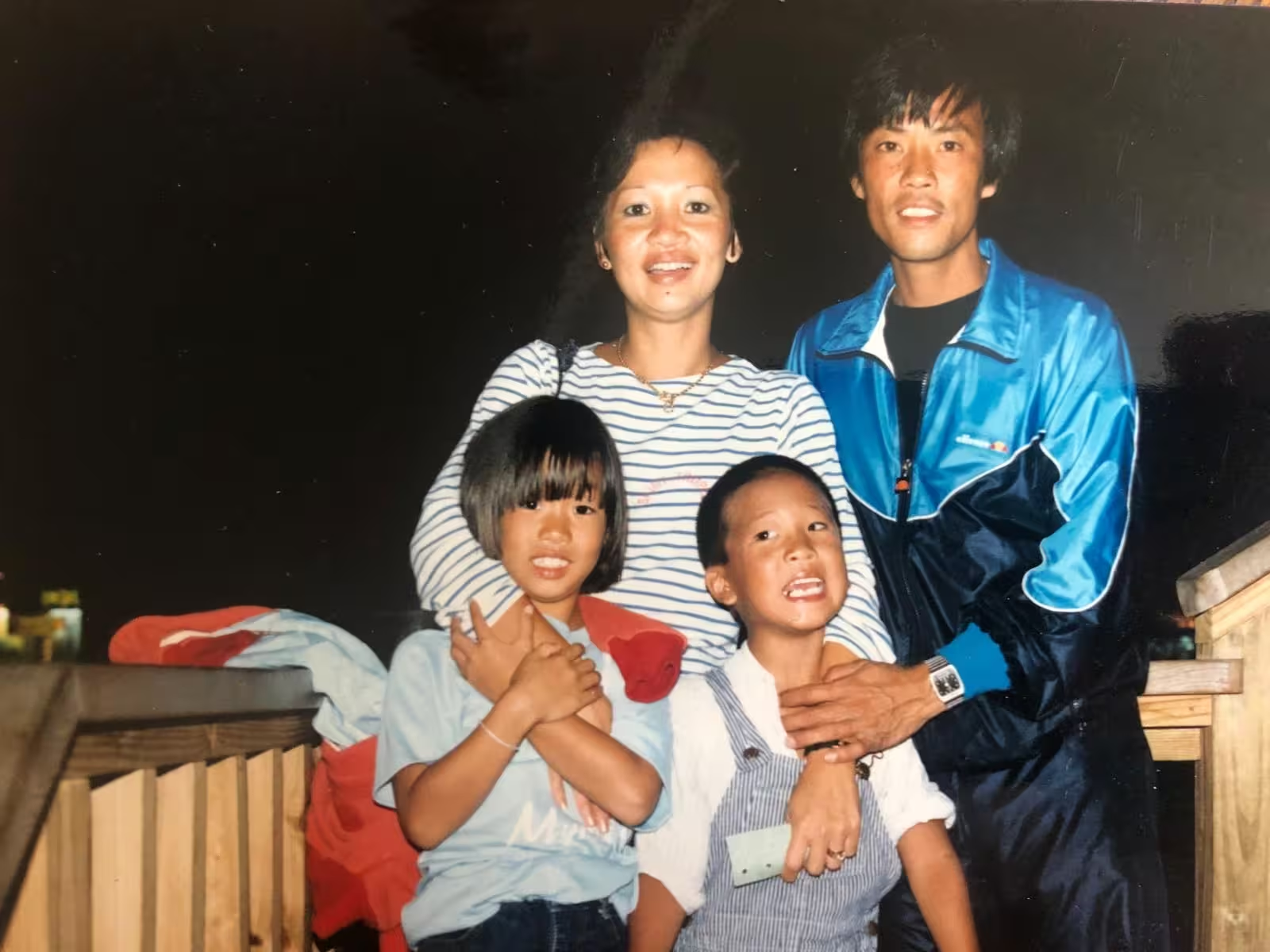

Elizabeth Ai and her mother. Image courtesy of Ai.

For years, I have refused to watch American-made films on the Vietnam War. I still haven’t seen Apocalypse Now (1979) or Platoon (1986) or Full Metal Jacket (1987), canonical works that are, so I am told, “important” and “great.” This is not to protest these films and their makers, or reject the authenticity of their stories, their right to be told. As an American-born daughter of Vietnamese refugees, I feel I must maintain this stubborn resistance so that my inherited memory of the war—what some Vietnamese people call the American War—can remain pure, untainted by the U.S.-centric stories that dominate its cultural memory.

I want to honor what my family lived through, experiences that are often sidelined in films about American soldiers. “We’d survived a war / to be cast into the margins / of our own story,” wrote the poet Cathy Linh Che in Becoming Ghost, 2025. In this collection, Che channels the voices of her parents, who she says were extras “like the scenery” in Apocalypse Now. Yet I am desperate to look ahead, beyond the talk of war that tends to reduce Vietnamese identity to trauma’s bare roots. There is a striking tension to this experience, which has been echoed by the respondents below: How do we navigate an ethnic identity that is not solely bound by war, while also upholding its collective memory? How do we make a space where our voices, as refugees and children of refugees, carry significant weight?

I see the 50-year anniversary of the Fall of Saigon this month as an occasion to bask in the diaspora’s narrative plenitude, to recognize the myriad ways in which Vietnamese identity is being made and made manifest. Still, any commemoration of Vietnam must also acknowledge that war is an omnipresent state of affairs in the U.S., even during periods of relative peace. I am reminded of the work of photographer An-My Lê, which highlights how the American relationship to armed conflict is understood mostly through images. War, then, becomes an abstract event occurring beyond national borders, despite active American intervention in places like Palestine, Syria, Yemen, and Somalia. Even when conflict is out of sight, whether in the present or the past, traces of its violence linger on. I place my hope in the dialogue that is emerging from this moment, among parents and children, across creative communities and generations, that will inform the next 50 years to come. Here's what that moment represents for seven other diasporic creatives.

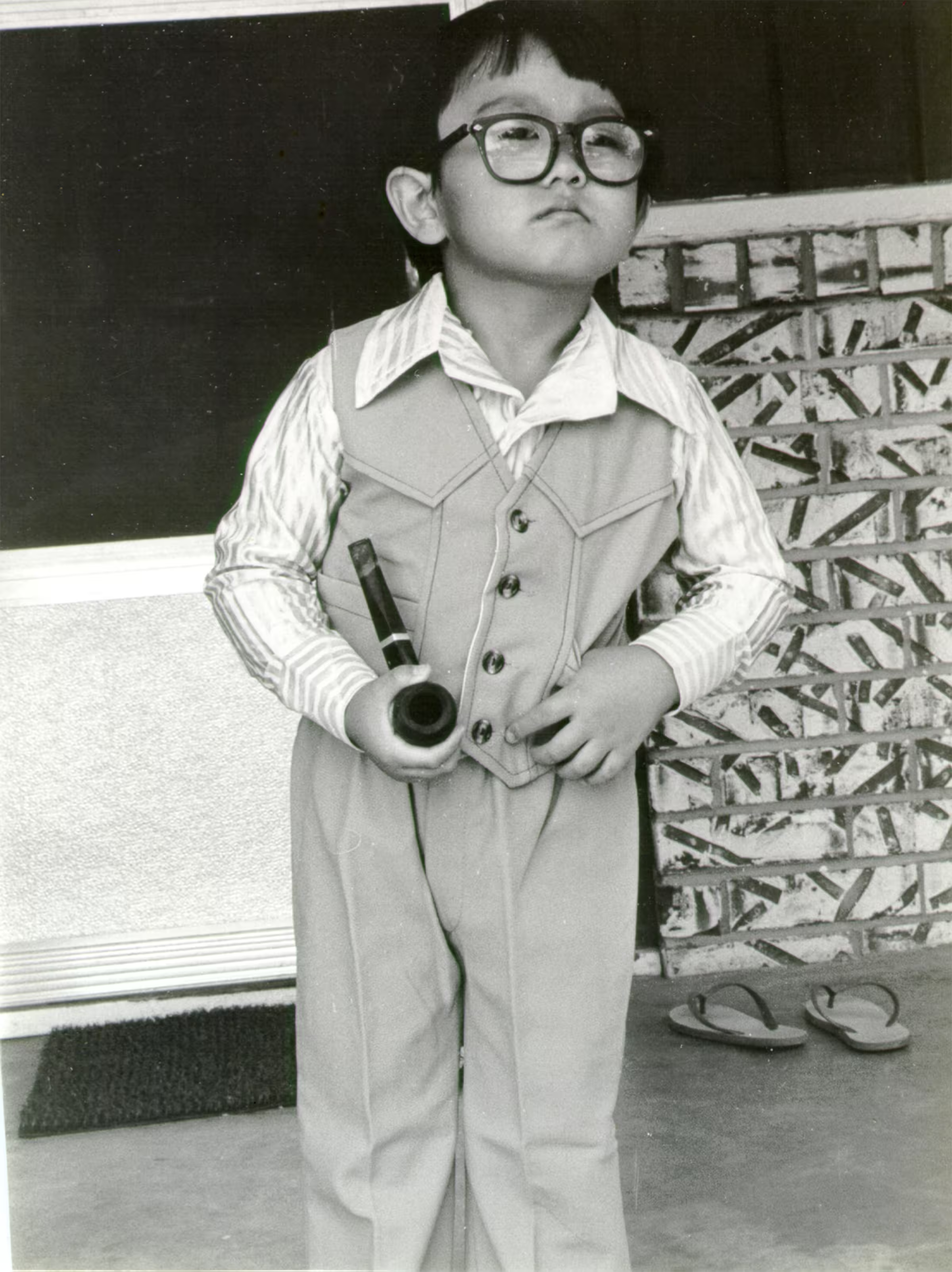

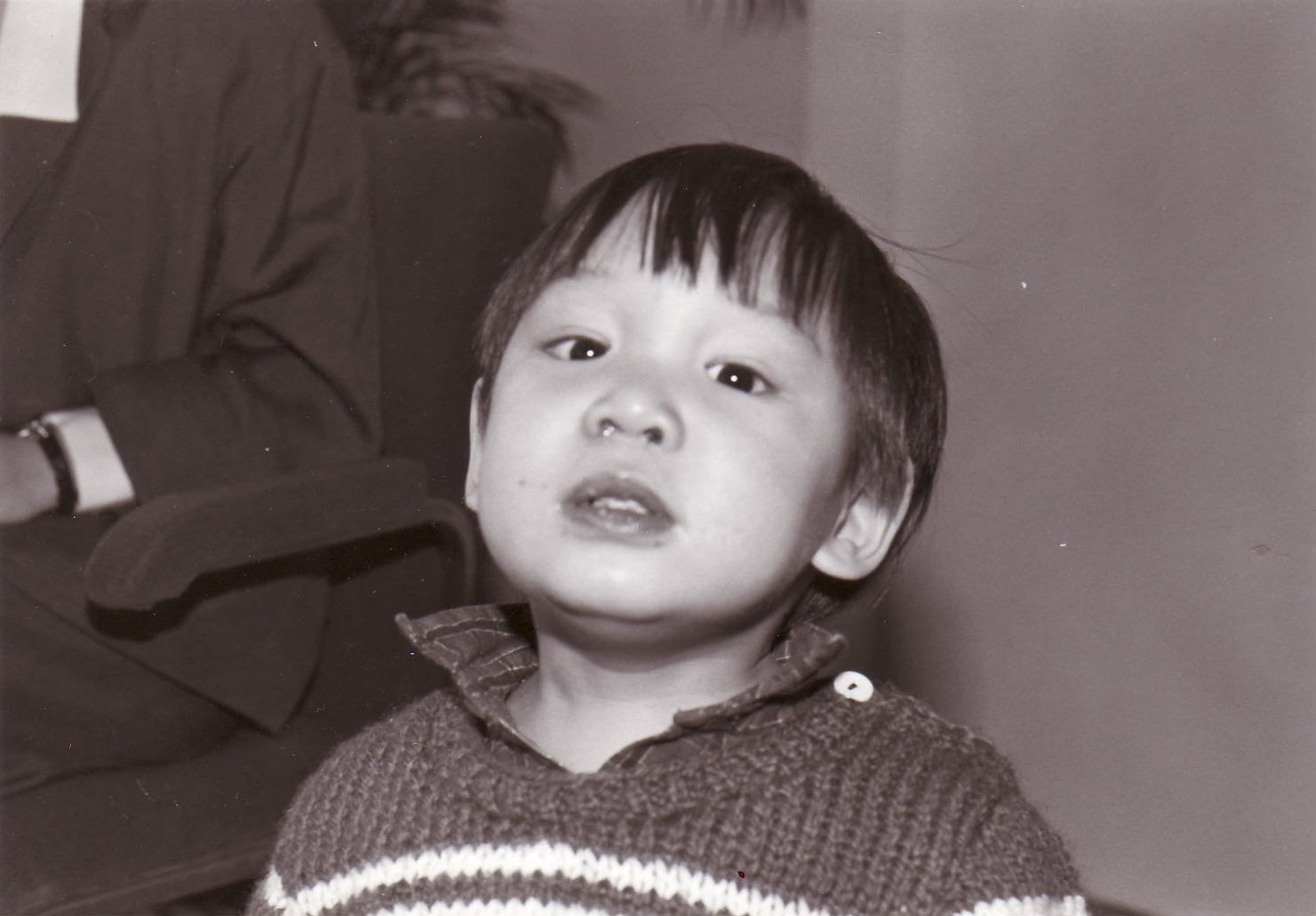

Tuan Andrew Nguyen as a child. Photography by Nguyen's father. Image courtesy of Nguyen.

“Rather than considering anniversaries solely as times of celebration, how can we effectively utilize anniversaries as moments of reflection and introspection? Civil war devastates and ravages a people, a country, in the deepest and most traumatic ways. We mustn’t forget that the war in Vietnam was a proxy war between superpowers who both saw Vietnamese lives merely as instruments for the advancement of their own political agendas. Each side fueled the violence of war by pushing fear—fear of communism, fear of colonialism—making brothers suddenly become the other and the enemy. Instead of celebrating victory or mourning the loss of a country, maybe we can take a moment to reflect upon the outcomes of fear and the devastation that comes from allowing fear to overcome our need for compassion and solidarity.”

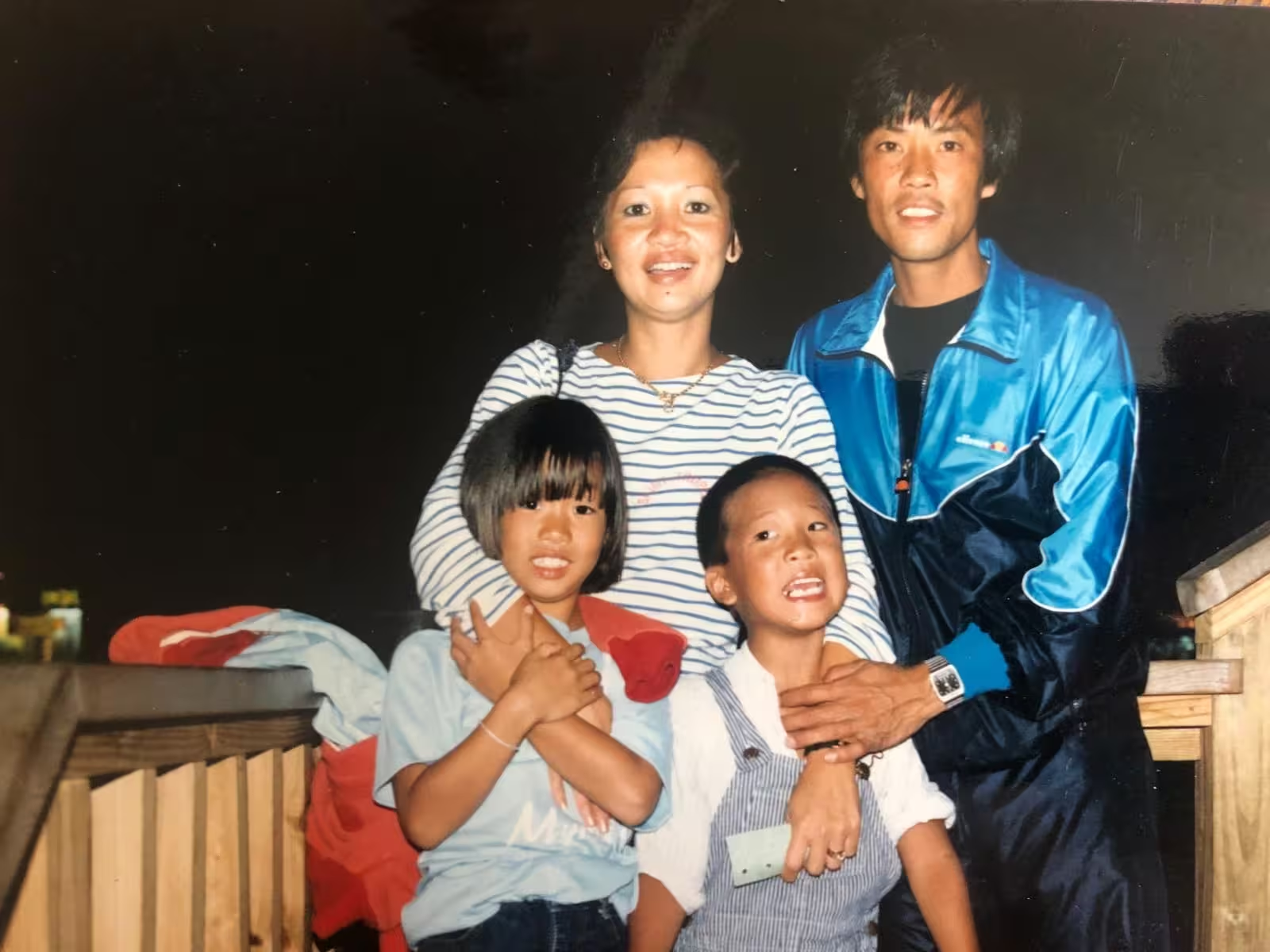

Hung La as a child with his family. Image courtesy of La.

Hung La, fashion designer and founder of Lu'u Dan

“Like a lotus rising from the muddy waters, I am a flower born from the aftermath of the Fall of Saigon. I was born in America a few years after, and through unspoken words and silent tensions—brushed-over emotions, hatred, and even disgust—I inherited a legacy that was never clearly named. My parents, their parents, all of their family members and all their friends were uprooted and forced to emigrate to foreign lands. It's not something I can claim as lived experience, yet it’s something I live with every day: Both of my Vietnamese parents met in America, and I would not be here if it hadn’t happened. This anniversary marks a significant moment—when the Vietnamese people reunified their country without the dominance of external powers. Yet the truth is more complex. It was a resolution layered with pain, trauma, and wounds that remain unhealed and untransformed. Fifty years later, Vietnam and its people continue to show remarkable growth, resilience, and strength. As I reflect on this moment, I carry both sorrow and gratitude. My grandfather was Bùi Diễm—a politician, mathematician, film director, founder of The Saigon Post, and ambassador between Vietnam and the United States during the Vietnam War. He fought passionately against the North Vietnamese, advocating for the democracy and freedom of the South. One of his core beliefs about the complexity of the Vietnam War was that it was shaped by deep misunderstandings on many levels, from all sides involved. I remember him once saying, ‘It wasn’t just a war of weapons, but a war of misread intentions.’ That sentiment has stayed with me—his ability to hold conviction while still acknowledging complexity and pain. As we mark this anniversary, I think it’s important to recognize that even after 50 years, there is still much to learn and understand.”

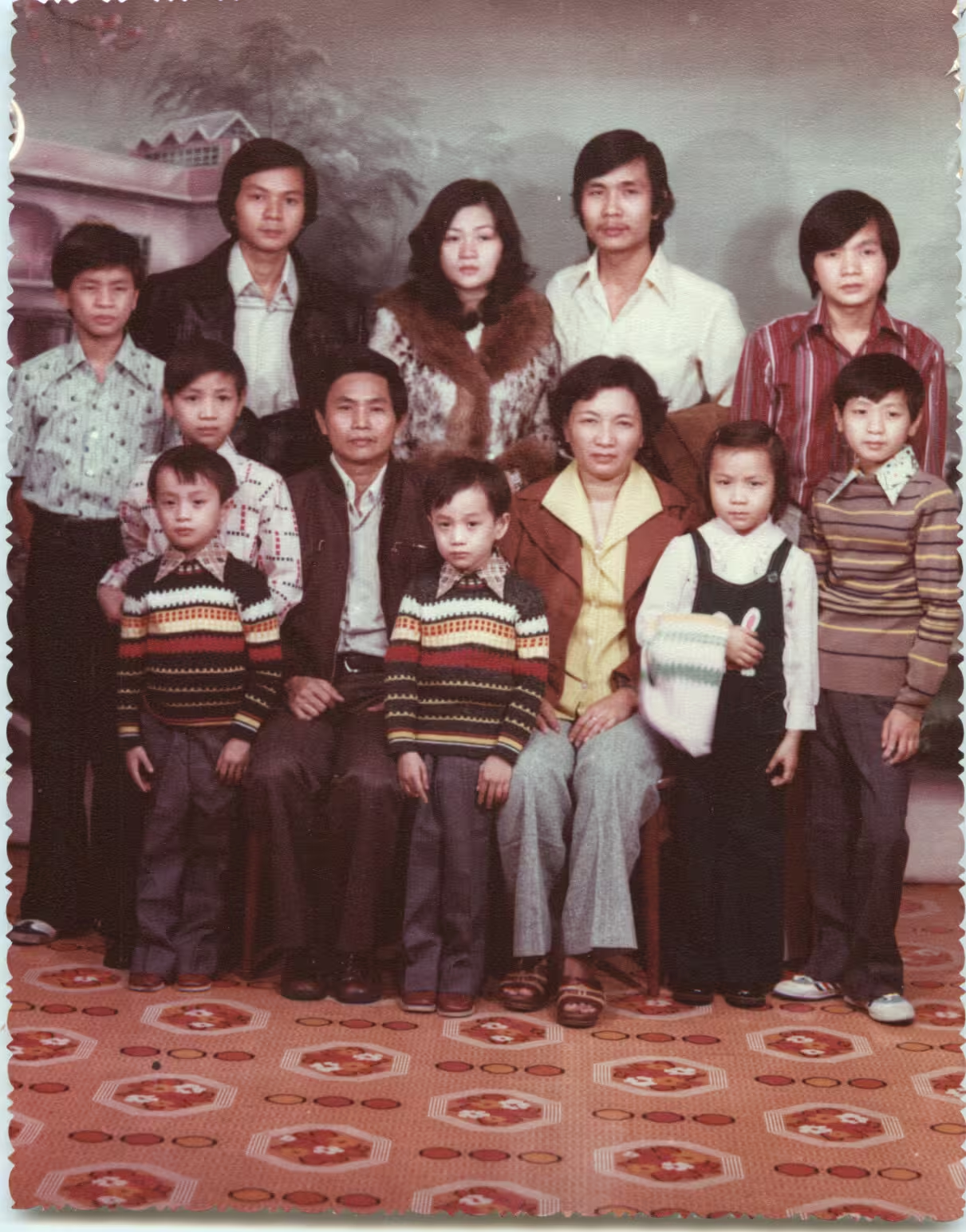

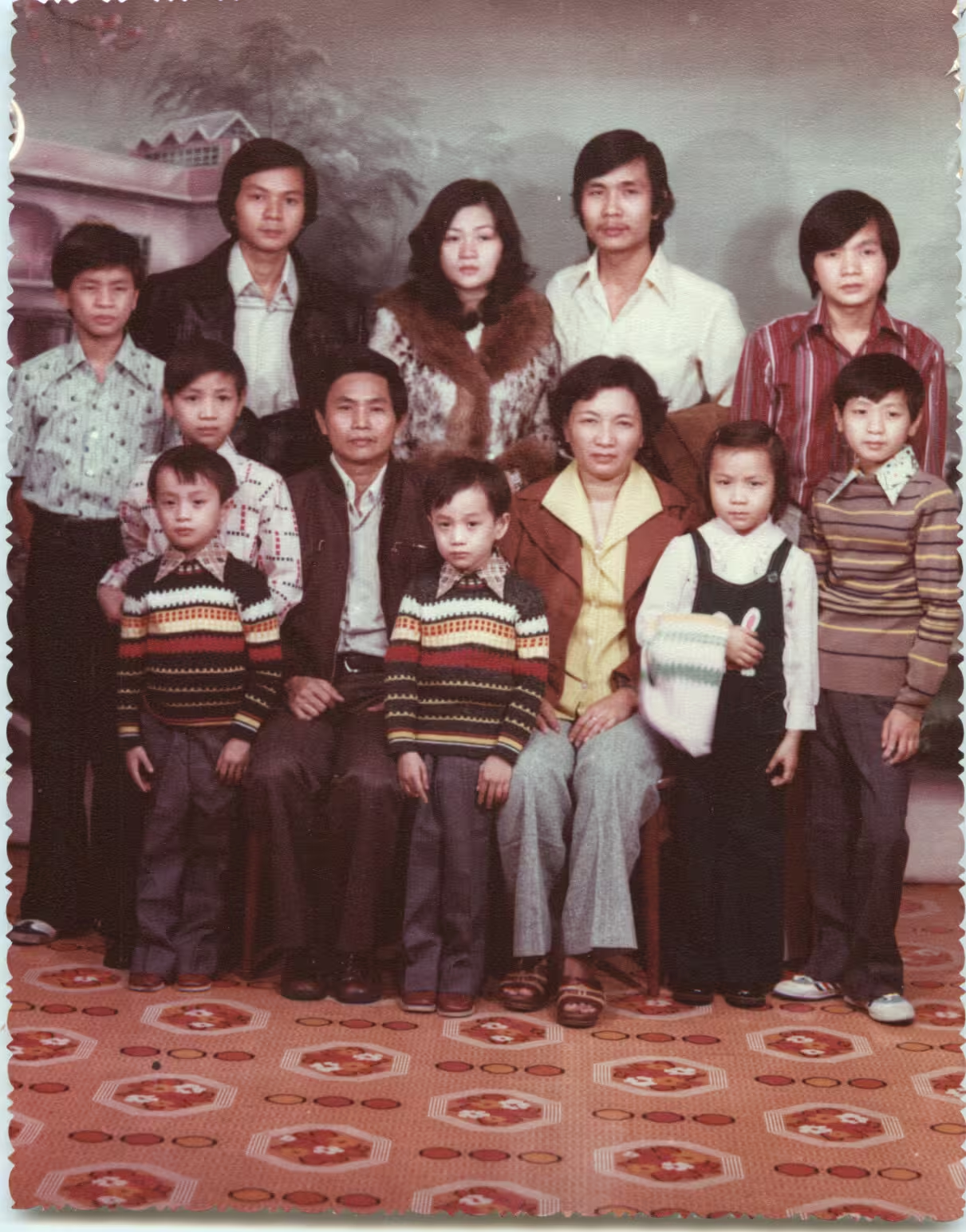

Elizabeth Ai's mother and her family in Hong Kong after fleeing from Vietnam, after her grandfather (front row) was released as a prisoner of war. Image courtesy of Ai.

“Anniversaries can be complicated—especially when they mark something as traumatic as the end of the American War in Vietnam. The word “anniversary” suggests something contained, reflective, maybe even celebratory. But for many of us in the Vietnamese diaspora, it’s anything but. In my work, especially with New Wave: A Documentary (2024), I’ve been drawn to what we inherit emotionally—not just history, but the silence that follows it. The war and our family’s displacement from Vietnam was never something that was directly explained to me growing up. My questions were often dismissed; it felt like I was forbidden to be curious about our past. That silence carried its own weight, and for years, I didn’t know what to do with it. What I’ve come to realize is that allowing ourselves to feel, really feel, is in itself a form of resistance. It’s a counter narrative to the expectation that we tidy up trauma, make it palatable, patriotic, or easy to digest. Feeling our grief, our anger, our longing, that’s how we begin to unpack the silence that’s shaped us, and hopefully start to transform it. This 50-year mark isn’t about national memory or even just family legacy. It’s about asking: What have we been made to carry? What stories got buried? And how might we finally give voice to what’s been hidden? Art gives us a place to do that. It doesn’t resolve the past, but it helps us live with it—and maybe even honor it. And in that complexity, I think we start to find a way through."

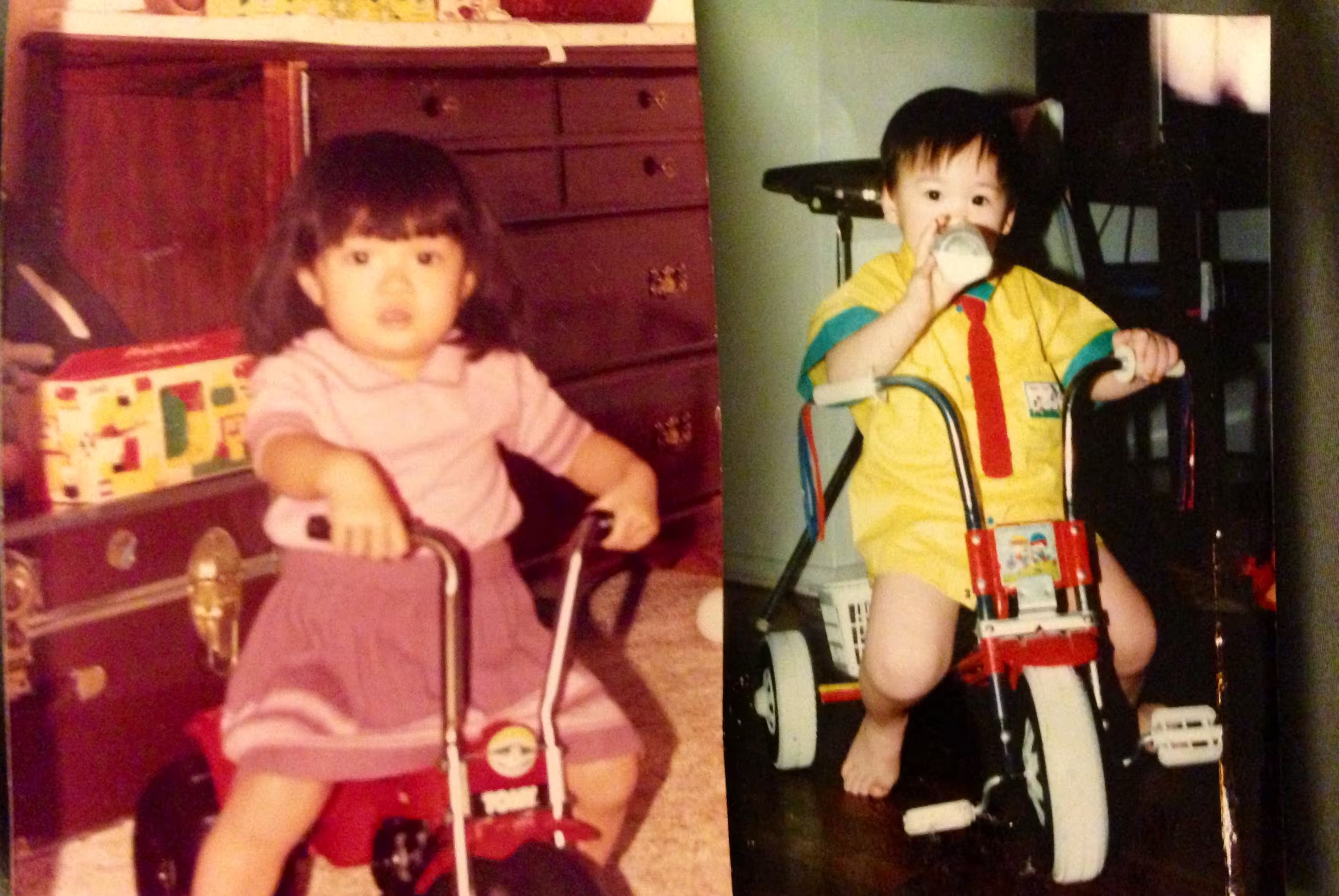

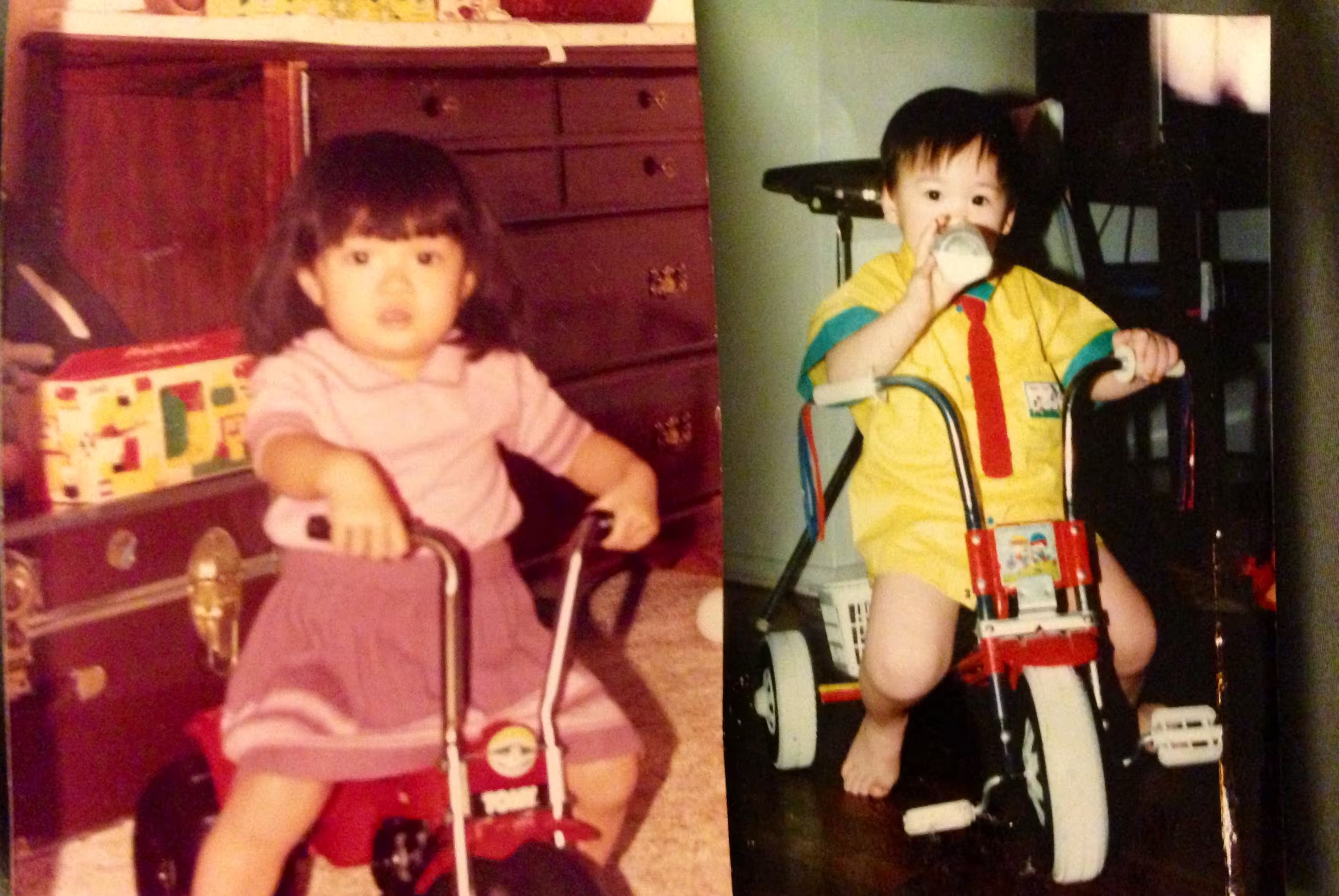

From left to right: Yen Vo and Jimmy Ly as children. Image courtesy of Vo and Ly.

Jimmy Ly, chef and co-owner of Madame Vo

“An anniversary, especially one tied to something as heavy as the Fall of Saigon, doesn’t feel like closure. It feels like a reminder of everything unresolved: across generations, across oceans, and within ourselves. This 50-year-mark is complicated. It’s meant to mark time, to remember. But what exactly are we remembering? For many of us in the diaspora it’s not just a political moment; it’s a personal rupture. My parents escaped with nothing but fear and hope, and even though I was born here in New York, I carry that story in everything I do. I think anniversaries can be helpful if they create space for reflection, but we need to be careful not to freeze our community in trauma. We deserve to be seen not only for what we’ve been through, but for what we’ve become. This 50-year mark hits different. As someone who runs Vietnamese restaurants, writes about our food, and builds platforms for our culture, I constantly feel the tension between memory and movement. People still want to define Vietnamese identity by war—but that’s not the full story. The work I do is about reclaiming that narrative. It’s about showing the beauty, the creativity, the joy that has emerged from our community. This anniversary makes me want to push even harder to shift the focus from what happened to us to what we’ve built since. There’s so much unspoken trauma in our homes: parents who never wanted to burden us, kids who grew up feeling it anyway. And beyond that, I want to see us elevate stories about culture, food, language, joy—things we’ve protected and evolved. Let’s ask not only what we lost, but what we’ve saved. Let’s highlight the fullness of our identity, not just its pain.”

Tricia Vuong's father and his friends at Palawan Refugee Camp in the Philippines during a moment of joy and play. Image courtesy of Vuong.

“The 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War is a complicated one. I grew up with a particular narrative, shaped by my family’s diaspora story and memory. But as an adult, my education in decolonization has challenged what I once believed. I’m still grappling with how grief and trauma shape our understanding of history, and how it sometimes takes another generation to see that history differently. How do I honor my parents, refugees from South Vietnam, and the many others I’ve interviewed—their stories of loss, resilience, and survival—while also questioning the dominant narratives I was raised with? How do I hold space for the trauma of displacement while recognizing that Vietnam’s victory marked the end of centuries of colonization and imperial rule? Lately, I’ve been reflecting on a quote by Frantz Fanon that continues to echo in my thoughts: ‘Decolonization is inherently violent.’ It’s essential to mark April 30 not with a single story, but with the full spectrum of experiences it represents. And it’s just as important to examine what it means to be an American citizen today, with all the contradictions that identity carries. From Palestine to Sudan to the Congo, the struggles of oppressed people are interconnected. We remember not only the Vietnamese people’s struggle—but also the global fight for liberation and justice.”

Tue Nguyen as a child. Image courtesy of Nguyen.

“As someone born in Vietnam decades after the war and lucky enough to come to the U.S. in 2016, the 50th anniversary of the Vietnam War feels personal in a way history books can’t explain. I wasn’t born into privilege, but being here gave me chances I never would have had otherwise. My family doesn’t talk about the war much—not in the detailed way some families do—but they carry its memory in quieter ways. They focus more on preserving our culture through traditions, food, and values. I think for them, the anniversary is less about the war itself and more about reflecting on the long journey they’ve taken—what they’ve overcome, and where they’ve ended up. This isn’t just about the war—it’s about what followed: survival, migration, rebuilding. It’s about honoring those who lived through it, and recognizing how their struggle gave people like me a future. I think one conversation that needs more attention—especially within the Vietnamese diaspora—is mental health. So many in our community carry generational trauma from the war, displacement, and the pressure to survive in a new country. Yet, therapy and open discussions about emotional well-being are still seen as taboo or a luxury. We need to normalize these conversations and push for mental health resources that are accessible and culturally sensitive. Healing isn't just about physical safety or financial stability—it's about emotional recovery, too. That should be part of how we remember and move forward.

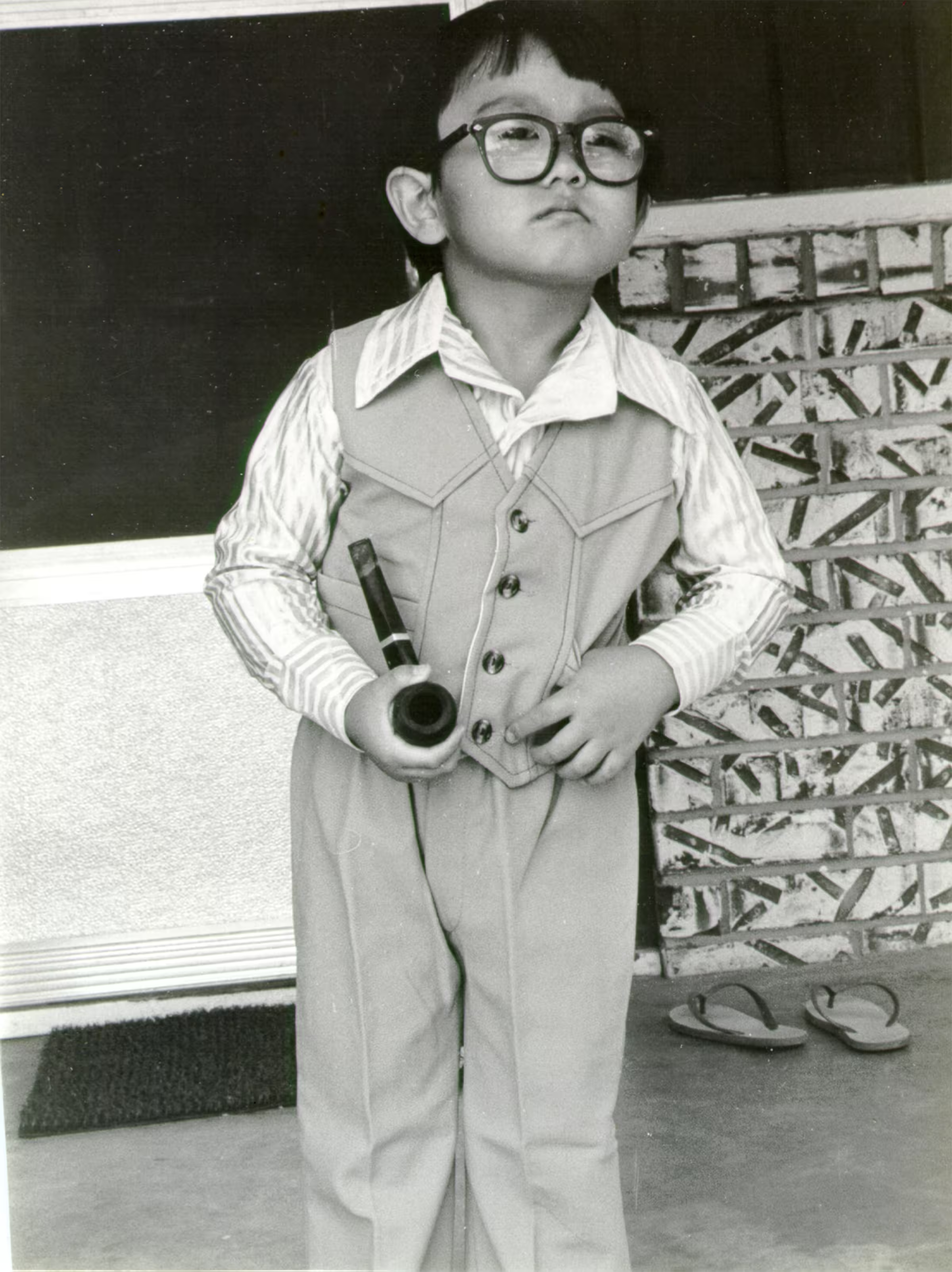

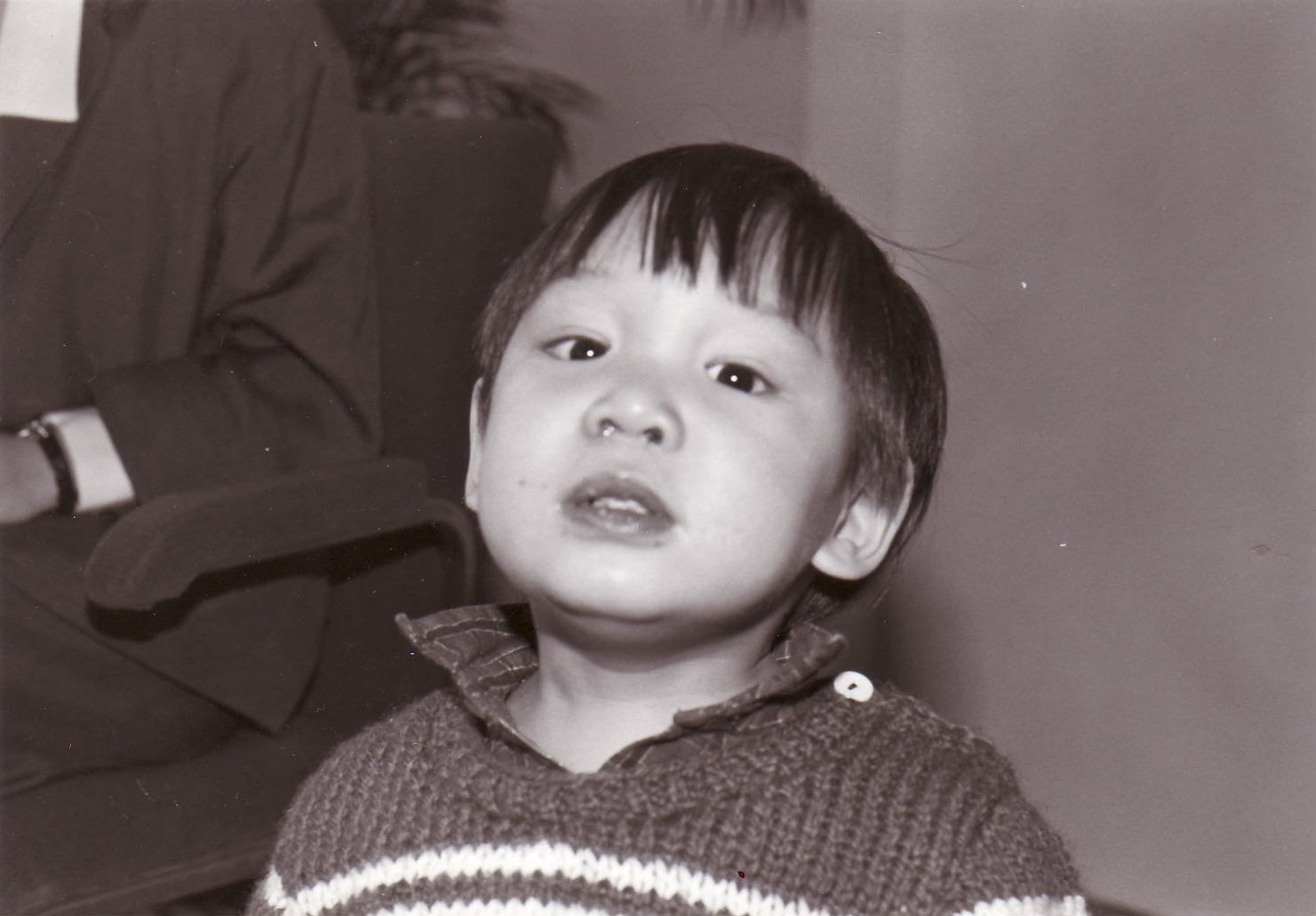

Kevin Nguyen as a child. Image courtesy of Nguyen.

“No one in my family is thinking about the anniversary. Fifty years is more of a political marker than a personal one. My father left before the Fall of Saigon, the rest of his siblings in the years after. We’re not doing anything to celebrate. What would we even do? Meanwhile, me and my Viet friends—the second-generation, mostly-born-in-the-U.S. writers, artists, and creatives—have never been busier. I just published a novel [Mỹ Documents], the timing of which was total coincidence, and all my promotion opportunities have been through the lens of the war (just like this one!). Last week I talked to an illustrator who said he’d never had this many pieces commissioned. We’re being called upon to commemorate a thing our parents lived through. I feel a sense of duty to say yes to everything because I do think the war has been mythologized in problematic, U.S.-centric ways. Earlier this year, Apple put out a documentary series called Vietnam: The War That Changed America—so we are still repeating the same fallacies. But there is something darkly funny about the Vietnamese American struggle to not be defined by the war, and yet here we are, volunteering to be good cultural stewards and historical ambassadors. I should call my parents and ask if they see the humor in it too.”