Vera Tamari’s Art of Resourcefulness

Since the 1960s, the Palestinian artist has made art that is personal and inevitably political.

At nearly 80, Vera Tamari is a doyenne of the Palestinian art world. Born in Jerusalem in 1945, she studied fine art at the Beirut College for Women (today’s Lebanese American University), ceramics at Italy’s National Institute of Art in Florence, and Islamic art and architecture at Oxford University in England. Despite Tamari’s travels, she has always returned home to Palestine. “I always felt linked,” she says. “Not like a heroine, but I have a big cause to come back to.”

Tamari’s work ranges in material, theme, and scale, from bas-relief clay dioramas, inspired by family photographs that forms the basis of her memoiristic 2021 book Returning: Palestinian Family Memories in Clay Reliefs, Photographs and Text, to massive and conceptual, including the installation Going for a Ride?, 2002. Such combinations of intimacy and abstraction—often ironic—defamiliarize themes of memory, tradition, and injustice while inspiring curiosity.

I didn’t know about Tamari until recent events prompted me to learn more about Palestinian art. My conversations with her aided this effort: Tamari’s personal experience as an artist in Palestine offers an oral history of some of the region’s biggest art movements of the last 50 years. She delivers it with casual lucidity, aided no doubt by her many years as a professor of art history and visual communication at Birzeit University in the West Bank, where she founded the Ethnographic and Art Museum, and within it, the Virtual Gallery, an online space to facilitate cultural exchange between artists within Palestine and those beyond. Started in 2005, it’s currently defunct due to lack of funding but remains a valuable archive and a testament to Tamari’s vision and resourcefulness. I ask her if she thinks it might someday be resurrected. “I always hope it will,” she says.

Rose Courteau: Where are you right now?

Vera Tamari: Ramallah. It is about 20 kilometers from Jerusalem, but to get to Jerusalem takes us a whole day, because we're not allowed to go as Palestinians. There are big checkpoints. You need a permit and stuff like that. It’s a big hassle and humiliation. I haven't been in Jerusalem in five years. The whole situation in the West Bank is so very low, depressed, and sad. We're just onlookers. I know some of the artists [in Gaza]. They have no food, no water. We live in one world, imagining how we can help them survive as artists, but they want to survive as human beings.

RC: I agree, there's something that feels farcical about a conversation about art right now.

VT: And yet it’s good! Through my book, Returning, I was able to talk about the Palestinian plight since 1948 and before the Nakba, and how Palestinians were living in cities like Jaffa and Jerusalem. Because I was very small when the Nakba took place— maybe two and a half—and I don't remember anything, it was important for me to put myself in through photographs [and] stories from my parents, who talked about the people in the pictures—the aunts, uncles, cousins, my mother. I'd like to talk about The Woman at the Door.

RC: Let me pull it up.

VT: The Woman at the Door is my mother. It was one of the first [of the ceramic “Returning” series]. My mother was very special. She was highly educated and very sensitive. [In the photo] she looks full of anticipation. After I did the relief work, I found a little amulet of hers in which she had folded paper from her diary. It was from the day before her wedding in 1940. She wrote about how she served her last night in bed in her own house in Jaffa. She said, “I don't know what the future will be.” My father was a collector of images and used to take family photographs. We were fortunate as a family to have kept these photographs, and I was lucky to be able to reconstruct some of the stories that I heard from them.

RC: Who took the photo of your mother?

VT: I don't know. I don't think it was my father, maybe.

RC: How long did it take you to make this work?

VT: I don't remember. Making it was very emotional. I felt very linked to the people and setting. Each relief probably went quite fast because I was enjoying them so much. I didn't do the whole series in one go. I did it over years.

RC: One thing I love about The Woman at the Door is her jaunty posture and the way that you managed to convey this sort of relaxed expectation with just a little bit of clay.

VT: That's what I felt. I'm not trained as a painter, but when doing these figures, I felt immediately the shape, the attitude came out naturally without fussing too much. The position, the postures, the different little daily gestures just struck me—how I was part of it.

RC: Would you like to talk about Home, 2017?

VT: It's completely different. Home is installed in the garden of the Palestinian Museum [in Birzeit]. I was commissioned [by the museum] to do a work on Jerusalem. Palestinians lived there for centuries. I made these steps [of Home] in the open, but caged. It's symbolic of being inaccessible. I had an opening in the top where the steps went up, towards freedom, eventually hoping that there will be access.

RC: What are the materials? How long did it take you to make?

VT: The steps are green plexiglass. Wire mesh is surrounding it. The design and planning took a long time, but the execution went very quickly because the technician with whom I worked was amazing. There was no light in the garden [when it was installed]. They had little torch lights, and I was watching them and telling them, “Oh, be careful, not that one!” But it's still there, and it's lovely because it’s surrounded by a lot of the natural landscape in the garden of the museum. Each season, flowers and plants grow around it. Sometimes in winter it becomes dull. Sometimes there are clouds, sometimes it's bright blue skies. The axis of the cube is in the direction of Jerusalem itself. That was very meaningful for me.

RC: I'd love to hear more about your different eras of artistic practice and how those have evolved.

VT: I started doing art in the ‘70s when there was a huge movement by the League of Palestinian Artists to do political art. A lot of imagery came out, especially in paintings, connected with issues of occupation and freedom: the symbol of the dome of the rock in Jerusalem, of the shackled prisoners breaking their iron, the land. I couldn't get too engrossed in the symbolism, so I shifted to studying Palestinian village life in the clay reliefs I did, to document and record the Palestinian women's embroidered dress, the crafts that they made. In the late 1980s, me and three other prominent artists [Nabil Anani, Sliman Mansour, and Tayseer Barakat] felt that everybody using the same symbols was repetitive. We started a group called New Visions. Rather than painting with oils, they would use mud and natural things. For me, it was also a shift in subject matter towards the person and the family through the family portrait. Then it happened that installation art started to infiltrate our way of reading. We had encounters with Mona Hatoum. She came here and talked about how conceptual art can address issues the indirect way. Going for a Ride, 2002 was partly [produced] because I had this background as a theater person. But I continued using clay within a bigger concept.

RC: When were you involved with theater?

VT: I studied drama as a minor in college. I liked directing and stage design. I was involved with a theater group in the ‘70s here in Palestine. We were all amateurs. There wasn't any theater, so this was just a very experimental group. I was in my early thirties, something like that.

RC: Where would you put on the plays?

VT: In schools or municipality halls. I remember one major thing we did in an unbuilt municipality. It was only the skeleton of the [building]. We brought in little chairs and there was no electricity, but the whole play was all based on that. We used candles.

RC: How have the political and material circumstances in Palestine influenced your art or the art scene there more generally?

VT: It's a big question. We started doing art without having colleges and museums and galleries in Palestine to support the art that was being produced. Most artists had studied abroad, either in Iraq or in Egypt or in Syria, and came back with foundations of art that were common in those [areas], especially in Iraq. This Russian socialist movement was affecting the style of painting, all very classical and well-studied. Because we didn't have art schools or museums, the visual background of the audience was limited. When they saw these paintings, they related to them, like in Mexican mural art. It wasn't elitist art. It was art that had a message. In the early times when we used to have these exhibitions in schools and municipality halls, you wouldn't imagine the number of people who used to come. They would go so close to the paintings to look and absorb and ask questions. It was a very special time, and necessary. Then New Visions started experimenting. Framed works started getting out of the frame, the materials changed, and the subject matter became a bit more abstract.

RC: Did that shift create tension between the New Vision artists and other Palestinian artists?

VT: I think it was looked at as a mutiny. But then the political scene changed a lot, and there was more exposure to the outside world. It was easier for younger artists to travel, study abroad and get involved in the international art scene. Eventually the League of Palestinian Artists dwindled and did have the same role as it had before. Artists still incorporate Palestinian-inspired themes. The last work I did was a big installation, Warriors Passed by Here [2019]. I started drawing landscapes on big, long Japanese paper. They were so beautiful. And I said, “This landscape also has been ruined by so many soldiers who have passed through, by the settlements, by the wall that's cutting through the fields, by the uprooting of trees, by Palestinians themselves building without any kind of proper planning.” And I made the helmets, representing the different civilizations by which Palestine was trespassed.

RC: What’s the significance of the olive tree in your art? Do you want to talk about the series Olive Tree Women, 2009-2019? Some of their marks conjure hair, maybe pubic hair, and others make me think of hatchet marks and bandages.

VT: The olive tree was always a symbol that Palestinians used. It's all over the landscape. The olive tree was linked with the farmer and the rootedness of Palestinians. It's majestic and solid. Some are thousands of years old. They're called Roman trees and have very twisted trunks. Time has given each trunk a personality. I felt they were very sensual, too. The curves in the trunks. I always felt they might be the torsos of women. It's like these figures [in Dance] are dancing in an open space. It's lyrical. Other ones are not as light, [like] Bondage. Sanctuary is more like a body that's holding something precious in a warm way, and it becomes like a holy place. Toward Dawn is a lifting upwards. The names came afterwards. I loved working on [Olive Tree Women] because it was a new medium for me. It’s on fabric, and I used dyes and water watercolor and chalks to work on them. I stitched fabric on fabric. I made different layers to give transparency and volume to the works. They're quite big, about two meters long by 80 centimeters in width. They hang in a series on a piece of paper with Plexiglass on top.

I did another completely different [work about] olive trees, called Tale of the Tree [2002] during the incursion in Ramallah in 2002. There were people whose livelihood depended on the olive trees. Every day in the papers one would read about the destruction of olive trees. I was very affected by that. Army jeeps were going, there was a curfew, and it was all very intense. I started modeling little olive trees. It was therapeutic for me, and in my mind I kept saying, “For every olive tree that's being uprooted I'm going to make a clay olive tree.” In the end I made hundreds, 600 or 650, all [in] soft, colorful tones, like a reverie for the future of the olive trees. They were all on a plexiglass base. It’s one of my favorite artworks, frankly.

RC: I have to ask about a poster you made for the current group show “Posters for Gaza” at Zawyeh Gallery in Dubai.

VT: I never did a poster in my life. I couldn't even imagine an artwork that would really relate the feeling of what's going on in Gaza. It's too much. So I felt like expressing the destruction formally, in an abstract way. And also the light and hope. This combines both. It’s collage—tracing paper and watercolor. I didn't put the title to it. I intended in the beginning to put a little saying by [the poet] Mahmoud Darwish. It doesn’t translate well [to English]. But then I felt it was cliché.

RC: The bottom of the poster reminds me of so many things: ashes, rubble, a hole.

VT: Exactly. The accumulation of so much grayness. When you see the new landscape of Gaza, you see dust and people who are gray. The houses are gray, the streets are gray, the donkeys are gray. So the collage uses a lot of grays, but you never can give the feeling of the destruction. I don't know if I was successful or not.

RC: The bright colors at the top make me think of pamphlets, raining down. It also makes me think of bombs, and confetti—something weirdly celebratory.

VT: A friend of mine saw something totally different. She said, “Ah, these are the light spirits of the children who have died and gone to heaven.” Some people said, “Ah, these are the shelling.” It's interesting how different interpretations can come.

.avif)

The Versace-iest Versace After Party

No one knows how to throw a party like Gianni Versace.

.avif)

All That and a Side of Fries

As award season finales with the 96th Oscars next Monday, Getty Image Fan Clubs looks at an underrated but ubiquitously-influential Hollywood ritual: the post-award show burger.

.avif)

Revisiting Marc Jacob's Campy, Christmas Parties

The fashion designer's parties are still iconic despite the last official shindig happening 15 years ago.

.avif)

Pill Popper

Remembering the short-lived art-restaurant by Damien Hirst that was anything but clinical.

.avif)

What did Jay-Z say to Nicole Kidman?

A look at one particular table from Vanity Fair's 2005 dinner for the Tribeca Film Festival.

Beauty is Key

One century ago, Svenskt Tenn made a colorful splash in the throes of Sweden’s modernism movement. Today, Maria Veerasamy is leading the design brand to new horizons, while honoring its legacy.

A Magic Carpet in Milan

For Milan Design Week, Issey Miyake honors the late Japanese fashion designer’s craftsmanship and legacy with a series of animated installations by the Dutch art collective We Make Carpets.

Birds of a Feather

Christian Dior spent his childhood enamored with Japanese art and translated its sensibilities into his legendary designs. Now, Cordelia de Castellane has found new life in his bird and cherry blossom motifs.

A God Called Time

Fueled by curiosity, the late Gaetano Pesce’s radical, multidisciplinary approach to making carved a path for a new generation of polymaths, including trailblazing artist and DJ Awol Erizku, with whom he shared one of his final conversations.

.avif)

Angelo Flaccavento’s Simple Rice

The fashion writer opts for a simple and elegant rice dish. The twist? A splash of lemon.

.avif)

Anastasiia Duvallié’s Home Away From Home

The New York-based photographer shares her recipe for scalloped potatoes and roasted autumn vegetables, a minimalist pairing that brings her comfort whenever she’s in need.

An Old El Paso Chili

Larry Bell's chili resurrects memories, submerged in a sea of spice and flavor.

.avif)

An Evening at Atelier Crenn

In San Francisco, Veuve Clicquot and Dominique Crenn’s flower child of a dinner party sets the stage for the Champagne maison’s latest vintage.

Activists Can Like Champagne, Too

Ruinart toasts to its year-long artist collaboration program with a Frieze LA dinner celebrating Andrea Bowers and her dedication to environmental justice.

.avif)

An Elegy for Commerce, an Ode to the Commerce Inn

To drop into New York's The Commerce Inn mid-dog walk and sip a tavern coffee with whisky and maple in one of the wooden booths on the bar-side of the quirky restaurant on a Sunday morning is the best version of stopping by a neighbor’s just to say hi.

.avif)

10-Minute Lime Cracker Pie

Stylist Daniel Gaines turns to this nostalgic recipe as an easy-to-make dessert when entertaining at home.

.avif)

A Martini Fit for a Matriarch

David Eardley’s grandmother has influenced his taste from design to cocktails.

%20(1).avif)

(Not Too) Sweet Rice Cakes

Michelle Li shares the recipe for her mother's nian gao with red bean.

Closing Time

Finnish-born Tiina Laakkonen has bested all aspects of the fashion industry. Now that she’s sunset her iconic, minimalist Hamptons boutique, what’s the shopkeeper to do? Everything.

Finally We Meat

For the last four years, I've gone to sleep with and woken up beside Sophia Loren. More specifically: a life-sized poster of the actress and a giant sausage from the film La Mortadella hangs across her bed. The only thing crazier than the plot of the absurdist 1971 movie is the fact that I've never seen it—until now.

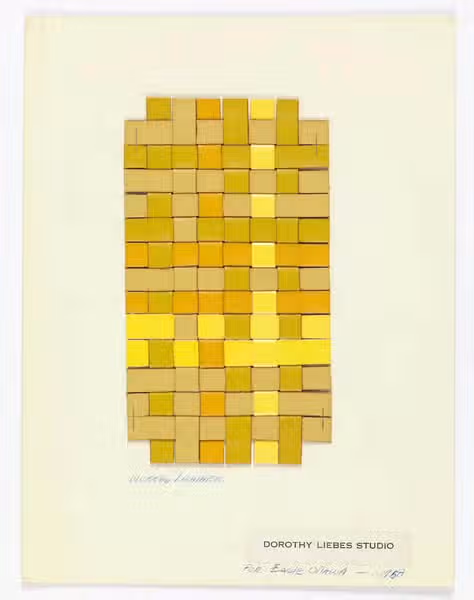

Call Me Mother

American textile designer Dorothy Liebes was one of the most influential textile designers of her time, so why don't more people know her name?

An Ode to Enya

Is she sleepy or slept on? A deep-dive into the work of the New Age singer-composer reveals a better understanding of her impact—and my dad’s taste?

Vera Tamari’s Art of Resourcefulness

Since the 1960s, the Palestinian artist has made art that is personal and inevitably political.

The Afterparty

Trailblazing artist Judy Chicago opens up about her New Museum retrospective and her 60-year-career built on taking up space.

The Sun Never Sets

Palestinian artist Yazan Abu Salame uses a variety of materials—and a background in construction—to explore the psychology of separation.

A Tonic To Boot

Cult grocer Erewhon dips its toe into footwear with a new collaboration with UGG.

A Man, a Woman, and a Bag

Almost six decades after its original release, a French New Wave classic is recreated in a new short film for Chanel. Directed by Inez van Lamsweerde and Vinoodh Matadin, the tribute brings together Penélope Cruz and Brad Pitt on screen for the very first time.

A Mother’s Creative Legacy

Lafayette 148’s new capsule collection with Claire Khodara and Grace Fuller Marroquin commemorates the life and legacy of their artist mother, Martha Madigan.

.avif)

Croc Over and Die

Samantha Ronson has a love-hate relationship with her shoes that she can’t take off.

I'll Have What He's Having

Vegetables with Paul McCartney, eggs with Lady Gaga, and kimchi alone: Mark Ronson offers a glimpse into his music-filled life to sister and fellow DJ Samantha Ronson.

.avif)

A Love Letter to Us All

This year I choose as much love as possible for Valentine’s Day. And Sugar.

.avif)

Samantha Ronson Turns the Table

After a life of cocktails and take-out, the DJ-musician has found a new relationship with food. And it’s f*cking delicious, as she writes in her new column for Family Style.

.avif)

Recipe for a Disaster-Light Thanksgiving

Samantha Ronson has endured the crazy, so you don’t have to.

A Toast to Napa

Between the bountiful California vines and the centuries-old oak trees, Family Style kicks off a quartet of intimate cultural dinners around America in ripe Yountville, California.

White Cube Cuisine

A gallery is more than just a space to view art; as Family Style's third Heart of Hosting dinner proves, it's also a place to come together.

Dining with Purpose

At a landmark Manhattan farm at the end of New York Climate Week, Family Style hosted a sensorial round table for the urgency of climate action and the celebratory spirit of a shared meal.

Spirited Design

Fittingly, Family Style's finale to its four-dinner fête centered on hosting culminated at Beverly's, a specialty boutique focused on the home.

Luxury Group by Marriott International's Chic LA Art Week Fête

Awol Erizku, Annie Philbin, Casey Fremont, Tariku Shiferaw joined Marriott International's Jenni Benzaquen and artist Sanford Biggers at one of Los Angeles’ most iconic institutions for a lush dinner by Alice Waters celebrating art and travel.

Summer 2024 Editor's Letter

Family Style No. 2 explores how the objects we surround ourselves with can tell us more about ourselves.

Objects of Affection

At Salone del Mobile 2024, Family Style presented a first look at the magazine's Summer 2024 design issue in the form of an ephemeral exhibition with Sophia Roe and DRIFT.

Xiyao Wang Dreams in Charcoal

The China-born, Berlin-based artist is in a constant state of flux; as her career continues to reach new heights, her style is also ascending. Now she's crossing a new horizon with her first debut show in the United States.

You Are What You Eat

As the natural world rapidly transforms due to anthropogenic impact, Cooking Sections have developed an approach that fuses art and research to imagine sustainable consumption. They call it “climavore.”

Bibliophilia Bunker

Inside High Valley Books, the basement bookshop for magazine nerds and moodboard queens.

Low Risk, High Reward

In her new Family Style column, Whitney Mallett investigates the prep power of Buck Ellison's art book—making sense of Brandy Melville and American exclusion trending in an election year.

I Need a Colada

At the climax of Art Basel Miami Beach, Whitney Mallett takes a dip into local legend Dalé Zine.

Spooky, Scary

Trick-or-treating at Climax Books’ New York expansion reveals a vault of goth obscurities and witchy reads.

_result_result.avif)

A Bientôt, Paris!

Ahead of the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games, Louis Vuitton pays homage to the French capital’s sports scene with an exclusive edition of its City Guide series as well as the first-ever City Book.

Is Delicacy a Choice?

The search to understand our collective desires may lie in the psychology of decision.

24 Hours at Hotel Chelsea

The iconic New York hotel is even more magical post-renovation.

Åsa Johannesson’s Web of Rebellion

The Swedish writer and artist takes a layered approach to exploring 27 groundbreaking photographs by LGBTQ+ artists in her first book.

.avif)